Our moral standards are constructs developed from our moral values.

A moral value is a system of thought we discover to make our lives better. It begins with having a purpose or quest. When we journey on fulfilling a purpose, consciously or unconsciously, any actions or behaviours we discover to fulfil that purpose, we count them as being good, and any behaviours in obstruction to that purpose, we count them as being bad. Through fulfilling purpose, we measure what is right and wrong for us, or righteous and sinful, from which we develop our moral values to living better lives.

On an individual basis, our moral values are selfish, self-righteous, or self-centred, because they fulfil only our personal interests. When however, we come to live in a community, we collectively agree on which of our individual values are selfless, then to constitute them as a moral standard for the community. This moral standard for the community now becomes a part of culture, to influence our offspring inherently.

This process defines loosely how we developed the moral standards of our communities. If a particular behaviour in society made the community better, we counted it as righteous, and if it made the community worse, it was then sinful. This simple understanding of the process to developing our human morals regrettably ends here. Hereinafter, it increasingly is complicated.

The Righteous Behaviour.

If a righteous behaviour in the community, happening occasionally or repeatedly, came to achieve something revolutionary or miraculous, we then elevated the status of that behaviour from righteous to sacred. For example. If a person’s goodness extended to ten or a hundred people, we regarded them as righteous, but if it extended to a thousand people or more, they then achieved the elevated status of sacred, being as a saint, or as someone or something reverenced.

The Sinful Behaviour.

If a sinful behaviour in the community, happening occasionally or repeatedly, came to achieve something apocalyptic or threatening to the lifespan of the community, we then elevated the status of that behaviour from sinful to an abomination.

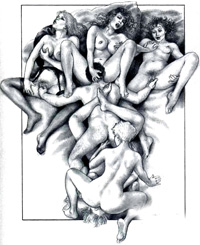

For example. If sex outside marriage was a sin, we then regarded those having extramarital sex as sinners. If however, the sexual appetites of the sinners were increasingly becoming insatiable, being oversexed, always inventing newer sexual escapades, progressing from extramarital sex, to masturbation, to sex with toys, homosexuality, group sex, to animal sex, and seeking more, to the extent it affected the community’s ability to make progress in agricultural work and preparedness for war, or it was responsible for the decline in the numbers of childbirths, sex outside marriage then achieved the elevated status of an abomination, being as something poisonous or lethal, to be avoided at all costs.

Sunan Ibn Majah 2561-2562.

“Whoever you find doing the action of the people of Lut, kill the one who does it, and the one to whom it is done.” “Stone the upper and the lower, stone them both.” (Book 20, Hadith 29 & 30)

In almost every community, the penalties for sin were either incarceration, suffering, or ridicule, and the penalty for an abomination was death.

To complicate things further, from establishing our good behaviours as moral standards, we began to categorize occurrences and events happening in our environments as being either good or evil, and to constitute them also as moral standards. For example, if men easily fell into sexual temptation, simply from sighting the body parts of women, the community then required the women to cover their bodies, to discourage the men from sinning. Women covering their bodies therefore became a moral value of society, to prevent sinfulness in the community.

Another example. If it came to the discovery that eating a certain fish was responsible for the poisoned death of people in the community, not eating that fish then became a moral value of society, to prevent an abomination in the community.

The Holy Bible.

Whatsoever hath no fins nor scales in the waters, that shall be an abomination unto you. (Leviticus 11:12)

Through observing right and wrong behaviours, also good and evil occurrences in our environments, we developed the moral standards of our communities, but to complicate things even further, our standards, principles, and ethics, across all our communities, were different, because being in different locations, having different experiences, also developing different traditions, living under different circumstances, we all understood our environments differently.

In conclusion here, we must try to answer the following question. Are we intelligent enough to understand that our environments define our moral values?

#next